Australia Weather News

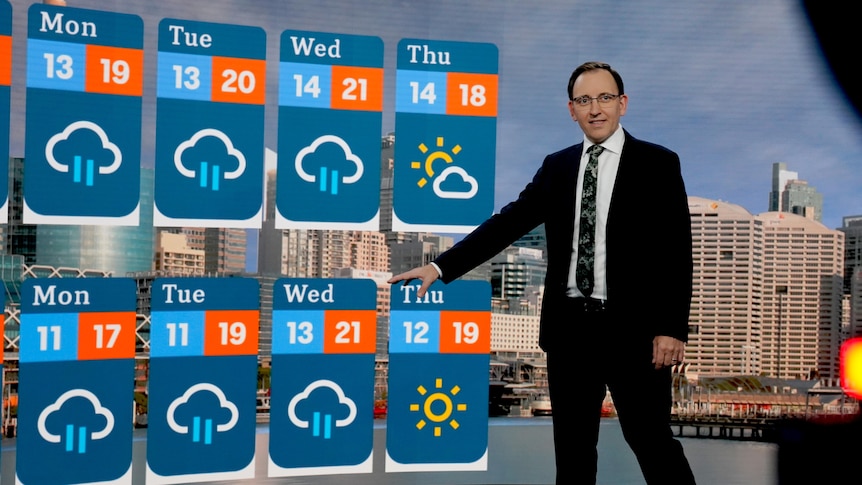

Meteorologist Tom Saunders believes weather forecasting has improved despite its critics. (ABC News: Esther Linder)

One of the most common questions I'm asked is how accurate weather forecasts are.

These queries are normally polite inquisitions; however, online comments on meteorological services can be far more hostile, even implying forecasts are borderline worthless.

Let's examine these claims, starting with how accuracy has changed with time.

Improving measures

Contrary to recent claims that climate change is making forecasting more difficult, an increase in computer power, detailed satellite data, along with an improved scientific understanding of the atmosphere, has greatly advanced the model simulations that are the basis of modern meteorology.

This has resulted in temperature forecasts improving by about one day per decade since the 1970s, and according to a Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) spokesperson, the advancements have become even more rapid in recent years.

"Forecast accuracy for maximum temperature has improved by two days in the last 10 years. This means that the four-day forecast issued today is as accurate as the two-day forecast issued in 2015," they said.

Significant improvements have also been made in other fields, like rainfall, wind and cyclone tracks.

The map below illustrates how weather models between 1974 and 2010 would have forecast the path of Cyclone Tracy, and there is little doubt if the storm was to occur today, Darwin would be given ample warning.

Are temperature forecasts accurate seven days ahead?

The two main fragments of a forecast most Australians consume are temperatures and rainfall.

The BOM's verification for maximum temperatures in the 2024-25 financial year shows the forecast was within 2 degrees Celsius of that observed 91 per cent of the time.

But how do we judge whether that's a skilled forecast?

Darwin residents with little meteorological knowledge could probably match that accuracy by just assuming tomorrow's maximum will hit the long-term average.

And in regions where the weather fluctuates, a forecast with a large error could still be beneficial — for example, if a location averages 25C, is forecast to reach 45C, but only reaches 40C, the forecast may have been 5C off but was still a valuable guide to possible threats like heat stress and bushfires.

That's why temperature forecasts require an initial baseline for assessment and one method to calculate the forecast error and compare its accuracy against climatology (long-term average for that time of year).

The graph below shows the forecast error (the blue line) in the Australian and New Zealand region from a leading global model compared to the climatological average (the red line).

[CORE: TEMP SKILL]Unsurprisingly, the further ahead the forecast, the larger the error; however, the key takeaway is even at nine days, the model is still more accurate compared to climatology.

This is compelling evidence that a seven-day forecast has skill and even suggests the BOM could be justified in extending to a nine- or even 10-day forecast as many weather apps already do.

Another method of assessing skill is to measure a forecast against the assumption that tomorrow's weather will be the same as today's (called persistence forecasting).

However, in the mid latitudes, where alternating warm and cold air masses can bring extreme fluctuations, the persistence system quickly results in large errors.

Take Melbourne, for example, in April 2025, using persistence forecasting for maximum temperatures reveals a mean error of 3.1C just one day ahead — that's severely inferior to the BOM's average error.

For a seven-day forecast, this error balloons to 5.1C, while modelling error that far ahead (just above the surface) is on average as low as 2.4C.

The same persistence errors for Sydney last month are 2.5C one day ahead and 3.1C seven days out, again less accurate than modelling.

BOM rain forecasts close to perfect

The bureau's rainfall forecasts are structured differently from temperatures, expressed as a chance of rain and a likely rain range.

Verifying the chance of rain is straightforward since the forecasts can be compared to the ratio of rain days that eventuate.

Data supplied to the ABC from the BOM for the 2024-25 financial year show that for the next day the rain probability forecasts are exceptionally accurate:

"The bureau's forecasts of the probability of receiving any rain were, in 2024-25, accurate to within 0 to 4 percentage points," a bureau spokesperson said.

Verifying the rain quantity is more complex since the given range is defined with the lower value being the amount that has a 75 per cent chance of being exceeded, while the higher value has a 25 per cent chance of being exceeded.

In 2023-24 rain totals one day ahead exceeded the lower value on 78 per cent of days and the higher value on 29 per cent of days.

In other words, the bureau's forecasts were accurate to within three to four percentage points, despite the fickle nature of rainfall.

"Routine assessments of forecast accuracy … show that the bureau forecasts are accurate and reliable, even given the high local variation in rainfall," the spokesperson said.

The bureau did not provide verification covering forecasts more than one day ahead; however, data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) below reveals rain forecasts are more accurate than climatology at least eight days ahead — indicated by skill values above zero.

[CORE: PRECIP SKILL]Why perception of accuracy doesn't match reality

If forecast data is highly skilled, as shown above, why then is the quality of predictions not unanimously valued?

Is it just selective memory, or perhaps a misunderstanding of forecasts and an unreliable method of self-verification.

The last two factors almost certainly work together to diminish the perception of accuracy.

For example, the BOM uses the term "high chance of showers" to describe a day when there is a 65 to 84 per cent chance of 'measurable rain'.

However, this forecast is often misinterpreted as 'a wet day' when in reality it implies up to a 35 per cent chance of no rain and covers the common scenario when rain only lasts minutes and is therefore missed by most people.

Temperatures can also be perceived inaccurately.

A 25C day in summer during periods of high humidity and light winds may feel uncomfortably warm in direct sunlight, while a 25C high in winter (when the sun's angle is lower) in combination with low humidity and strong winds could feel noticeably cool, particularly if the majority of the day was well below the maximum.

And one final word on weather apps.

A recent National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration study showed that apps were now easily the most popular source of weather data, but some provide hyperlocal forecasting to a level at which reasonable accuracy can't be expected — like giving hour-by-hour predictions up to 10 days ahead or daily forecasts up to 45 days ahead.

ABC